Scaling up Clean Household Energy

Introduction

In 2018, a Special Issue on Scaling Up Clean Fuel Cooking Programs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries was published as an initial effort to document, analyze and disseminate case studies on clean fuel and technology programs in settings across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The studies analysed in this volume offer some important early lessons and anticipate that a broad community of potentially interested scientists, policymakers and practitioners will find these of use in designing, evaluating and adapting related efforts.

Highlights

- Clean fuels for cooking, e.g. LPG, biogas, electricity, and ethanol/methanol, could provide public health benefits.

- Diverse clean cooking initiatives are being implemented around the world, but very few of these efforts have been analyzed.

- The Clean Cooking Implementation Science Network solicited proposals for case studies of clean cooking scale-up efforts.

- Eleven case studies were developed, spanning multiple fuel types and locations across South America, Africa, and Asia.

- Results suggest that programs require additional attention to monitoring and sustainability to maximize benefits.[1]

"While our focus in developing these case studies was to document programs most likely to yield health gains, this important goalis not the principal driver of most of the clean cooking programs we have profiled. Although health is often cited as a valuable outcome, most of these programs, and indeed most programs around the world today, are principally driven by economic development, environmental (forest) conservation, climate change mitigation and/or gender empowerment concerns (Goldemberg, Martinez-Gomez, Sagar, & Smith, 2018; Rosenthal, Quinn, Grieshop, Pillarisetti, & Glass, 2018)

One result of this mismatchis that programs may be missing important opportunities to maximize health, minimize associated costs, and integrate with other services. Multidisciplinary and multisector approaches to understanding barriers and facilitators to adoption and program implementation are clearly necessary, but coordinated national policies for household energy are still uncommon. Encouragingly, some country programs profiled here (e.g. Cameroon) have presented national energy “masterplans” that represent a step forward in inter-agency coordination. This follows advice provided by the sustainable energy for all (SE4All) community, which has recognized that coordinated national policies for household fuels are important: to provide a supporting regulatory environment, minimize perverse or conflicting incentives, and to maximize access to clean fuel options. It remains to be seen, however, whether clean cooking programs can be effectively designed to achieve the multiple goals they often cite."[1]

Generalized logic model for clean fuel scale-up

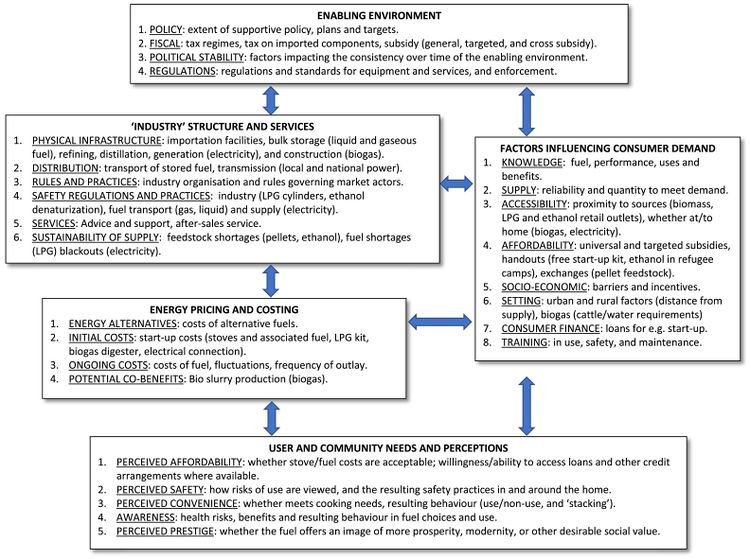

FIGURE: Generalized logic model for clean fuel scale-up.[1]

In this generalized version of the model, the same five main areas have been retained, based on the experience from the case studies:

- Government is key in setting the enabling environment, with the right policies, tax structures, and subsidy arrangements (where applicable); governments have a critical role in funding and managing these policies.

- Government policy and regulation will impact how the industry structure and servicesfunction, and their costs (and hence prices), but there are also aspects of industry operations that may be more or less outside the control of government policy. For example, interruptions in supply of ethanol, as seen with production from the main sugar factories in Ethiopia, may affect prices as well as availability.

- These policies also impact on fuel pricing directly, although there are other factors at work, including international prices which the government cannot directly control, e.g. for LPG, (although governments can smooth these if the LPG market is regulated, as in the case of Cameroon, Indonesia, Ecuador, etc.).

- Then there are factors influencing consumer demand, which are complex and partly independent of government actions. For eample, government may provide free start-up fuel and stoves as with LPG in rural Ghana and Indonesia, but in the Ethiopian refugee camps, fuel and stoves have been provided free by UNHCR and managed by Project Gaia. In the China study, farmers can exchange biomass feedstock for compressed pellets, thereby disposing of waste they are no longer allowed (by law) to burn, and reducing the cost of the fuel.

- Finally, there is a set of user and community needs and perceptionsaround prices and affordability. Although these perceptions are highly influenced by pricing, subsidy, etc., in other ‘areas’ of the model, community and individual-specific factors may lead to differences even among those with similar income and pricing profiles. For example, people used to buying wood, kerosene or charcoal at periodic intervals may view the prospect of saving up to buy a large LPG refill every few weeks more positively than people who are able to gather free fuel on a daily basis. People in different communities may also have differing aspirations for cleaner fuel based on marketing or other factors, or have contrasting experiences of fuel safety that influence their perceptions and habits.

Key questions emerging across the case studies

The study gives more details on the following questions.

- How can clean fuel be supplied in a reliable and predictable manner?

- How can we address the fact that households everywhere“stack” cooking technologies?

- What financing and leadership models will lead to the greatest impact, particularly for the most vulnerable?

How can Implementation Science help inform clean cooking program rollout and evaluation?

- What data gaps are most critical to address in future efforts?

What data gaps are most critical to address in future efforts?

Finally, the development of these case studies has highlighted several areas where critical data that would enable impact assessment, particularly for health effects, is notably missing. The three most critical areas of need are listed below:

- Improved fuel use indicator data in surveys. Historically, most programs have relied on cursory survey data to assess household fuel use. Questions documenting a household's “primary fuel,” while widely available and simple to collect, are not adequate indicators of use, exposure or environmental impact. Lucikly, progress is being made (under the leadership of the the World Bank and International Energy Agency) to deploy a multitier tracking framework (International Energy Agency (IEA) and the World Bank, 2015) that provides a more detailed assessment of secondary fuels and patterns of fuel usage to address all the major sources of energy for cooking, heating, and lighting within household. These more sophisticated survey tools will greatly improve our ability to assess risk from HAP exposure in a multitude of global contexts.

- Repeated measures to track sustained use. Beyond a focus on initial uptake, understanding consumer patterns of fuel use and stacking over a longer term (two to five-year period) is important to advance our understanding of how people respond to programs in a changing environment. For example, Asante et al. (Asante et al., in this issue) note that in the Ghana case, only 8% of LPG stove recipients report continued use of their stove 18 months post-intervention. Repeated measures of cooking behaviors in the same households at one, two and five years following the onset of a clean cooking program will be an important contribution to program evaluation and impact assessment. At least some of these measures should be objective, for example from heat sensors that are deployed as stove use monitors.

- HAP exposure measures. Substantially reduced personal exposures to fine particulate matter and other HAP emissions, to beneficially impact health, are the ultimate aim of the household air pollution community. However, evaluating exposure toward this aim is technically challenging, expensive and very time consuming. Developing simpler, more cost-effective tools for the non-specialist and/or developing reasonable proxies for exposure would be a significant aid to both the scientific and development practice communities. Personal air pollution monitoring in subsampled populations, as well as stove use monitors or time-activity diaries to better inform likely exposures, will also be important to help fill this important knowledge gap. Outdoor air pollution exposures also need to be much more explicitly measured and understood in the settings where household air pollution is problematic.

References

Further Information

- Scaling-up Strategies of Improved Cookstoves (ICS) [part of the GIZ HERA Cooking Energy Compendium]

- Result Based Monitoring of Cookstove Projects

- Risks in Energy Access Projects

- Publication - Scale and Sustainability: Toward a Public-Private Paradigm in Powering India

- Publication - Productive Use of Energy – Pathway to Development? Reviewing the Outcomes and Impacts of Small-scale Energy Projects in the Global South

- Publication - Energizing Finance: Scaling & Refining Finance in Countries with Large Energy Access Gaps

- Publication - Scaling Energy Access with Blended Finance: SunFunder and the Role of Catalytic Capital

- Publication - Scaling up Rooftop Solar Power in India: The Potential of Solar Municipal Bonds