Causes and Features of Watershed Degradation related to MHP Projects

Causes of watershed degradation

Deforestation and Destruction of Natural Vegetation

Overexploitation

Overexploitation occurs when arable land is used beyond its fertility potential without substituting the loss of nutrients by fertilizers or appropriate fallow periods[1]. Contributing to this overexploitation might be the shift from rainfed agriculture to modern agricultural methods, cash cropping and population growth. Overexploitation can lead to a variety of erosion features such as Gully erosion, landslides and alternation of discharge and should thus be prevented in order to provide sustainable use of the MHP.

Overgrazing

Overgrazing occurs when the number of livestock on a unit of land is too large. Resultant to this is the destruction of natural vegetation as well as soil compaction and erosion (cattle step). Furthermore the photosynthesis and hence biomass production and carrying capacity is decreased. Vegetation damages occur not only due to cattle bites, but also due to cattle step and pawing. Also the lack of a grazing plan which includes rotation of grazing ground, and, moreover, the lack of a national land use plan may contribute to overgrazing[2]. Like overexploitation, overgrazing can result in various degradation features such as alternation of discharge, change of soil moisture and gully erosion and thus might compromise the sustainable use of the MHP.

Unadjusted irrigation techniques

The implementation of irrigation techniques can lead to degradation, when the technical know how and/or the appropriate instruments are missing. Degradation, primarily in form of salinization, occurs in this case due to a bias between water inflow and outflow or the use of salty water[2].

Socio-economic and political causes

Various socio-economic as well as political causes can lead to land degradation. As mentioned earlier, population growth is a major cause of degradation, since it contributes to overgrazing, overexploitation and deforestation. Furthermore degradation occurs due to underdevelopment, since resources are often exploited to benefit developed countries and thus little profit is left in developing countries to manage or restore degraded areas[3]. Also rural-urban migration contributes to the occurrence of degradation, since urban populations need more firewood than rural populations. Hence the growth of urban populations in general goes hand in hand with an increase in deforestation and thus degradation.

Natural Causes

Not only human action can cause degradation to occur, but also natural causes such as the nature of rainfall (amount, intensity, variability, distribution…), soil (texture, structure, depth, moisture, infiltration rate…) and topography play an important role in the scope and scale of occurring degradation features. Under natural condition, soil erosion due to these causes is a natural process. However their negative effects can be amplified through human action (such as pastoral and agricultural land use for example) within the watershed[4].

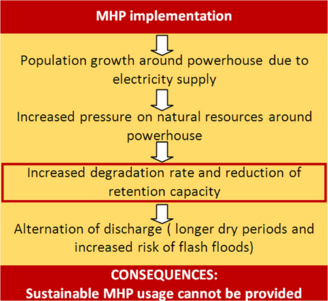

Note: It is important to note that most causes of degradation are closely interdependent and thus mostly more than one cause lead to the prevailing erosion features. In the context of MHP implementation, two aspects should be kept in mind in particular:

- The erosion potential is particularly high, when high intensity rainfall hits aridificated soils.

- The steeper the topography and the longer the slopes in the watershed the higher is the erosion potential[5].

Box 1

The MHP will particularly be affected by alternation of discharge and sediment load of the river. |

Box 2

It is important to note that most causes of degradation are closely interdependent and thus mostly more than one cause lead to the prevailing erosion features. |

Features of watershed degradation

Gully Erosion and Badlands

Gully erosion occurs when, during a rain event, laminar surface runoff becomes linear and strongly deepens small rills/riverbeds. The intensity of deepening depends on the slope and the ground texture/structure. Mostly gully erosion occurs where the vegetation cover is degraded and the infiltration rate is decreased. Badlands, an extreme form of gully erosion, form as full molds between wide gullies and are hardly or not arable[6].

|

|

| Badlands | Gully Erosion |

Streambank erosion

Apart from the vertical erosion in form of gullies, a further degradation feature is stream bank erosion, which is closely linked to increased runoff and associated alternation of river discharge. When land use changes, such as clearing land for agriculture, occur in a watershed, runoff increases and thus the stream channel adjusts to accommodate the additional flow, causing stream bed erosion. The process is further reinforced by the removal of vegetation buffers along the waterways to the point where it no longer provides for bank stability. Moreover, pastoral use along water ways reinforces this form of erosion[7].Stream bank erosion significantly increases the sediment load of the river, which not only results in the loss of fertile cropland but also negatively affects the sustainable use of the MPH plant.

| Streambank erosion in the Hagara Sodicha catchment (Ethiopia) |

Sheet and splash erosion

Due to the decreased infiltration capacity of the soil, surface runoff and thus sheet erosion increases. The process is further intensified by splash erosion, caused by the impact of raindrops hitting the ground[8]. A typical feature of sheet erosion is the laminar lowering of the surface, which is indicated by uncovered tree roots.

The MHP will be negatively affected by the resultant increase of sediment load of the rivers.

Landslides

Landslides may occur due to a variety of natural and human causes. Geological and morphological and thus natural causes can be, for example, weak or weathered material, contrast in permeability of material or shrink-and-swell weathering. Human causes on the other hand might include deforestation, land use change, excavation of slopes or irrigation[9].

The MHP will primarily affected by the increase of sediment load in the water caused by the landslide event. In case the magnitude of an event is big enough, the river might even be locked off completely, which could decrease or even stop the water flow and thus heavily affect the MHP use.

|

| Landslide in the Hagara Sodicha catchment (Ethiopia) |

Changes in soil texture and cattle step

Soil compaction is primarily caused by cattle step. Due to the decrease of pore volume, the infiltration rate decreases, which can, depending of the topography, lead to an accumulation of water or an increased surface runoff (and thus increased erosion potential)[10].

Just like changes in soil moisture, changes in soil texture will negatively affect the MHP use due to a decrease of retention capacity as well as an increase of sediment load.

|

| Cattle Step in the Hagara Sodicha catchment (Ethiopia) |

Effects of watershed degradation

Alternation of discharge

Alternation of discharge often shows in a decreased discharge amount or frequency. The latter often includes the occurrence of flash floods, which are short but very intense flood events. Alternation of discharge occurs due to a degradation of vegetation and the aridification of topsoil. Furthermore the process also increases soil erosion (due to floods)[2].

Alternation of discharge is the degradation feature which affects the sustainable use of the MHP the most, since without a continuous water flow, the electricity supply cannot be provided.

Changes in soil moisture and groundwater

Decrease of soil moisture and groundwater as well as a decrease of groundwater recharge are further features of degradation[11]. Due to the removal of the vegetation cover, the topsoil experiences an increase of evaporation and hence the formation of air spaces (aridification), which in turn reduces the water conductivity. This leads, on the one hand, to the creation of an evapotranspiration barrier, however, on the other hand it results in a decreasing infiltration rate and thus in increased surface runoff[2].

Changes in soil moisture and groundwater thus not only decrease the retention capacity of the soil but also increase the sediment load in the rivers which in turn negatively affects the sustainable use of the MHP.

References

- ↑ GRAINGER, A. (1990): The Threatening Desert: Controlling Desertification. London: Earthscan Publications Ltd.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 MENSCHING, H. G. (1990): Desertifikation: Ein weltweites Problem der ökologischen Verwüstung in den Trockengebieten der Erde. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Mensching" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Mensching" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Mensching" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ THOMAS, D. S.G./ MIDDLETON, N. J. (1994): Desertification. Exploding the Myth. Chichester, New York, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: John Wiley &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Sons.

- ↑ LAL, R. (1990): Soil Erosion in the Tropics: Principles and Management. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.

- ↑ MORGAN, R.P.C. (1999): Bodenerosion und Bodenerhaltung. Stuttgart: ENKE im Georg Thieme Verlag.

- ↑ LESER, H. (Hrsg.) (2005): Diercke Wörterbuch Allgemeine Geographie. Braunschweig: Westermann.

- ↑ Surry Soil and Water Conservation District et al. (undated): Streambank Erosion. In: Stream Notes, Vol. 1 No. 2.

- ↑ MENSCHING, H. G./ SEUFFERT, O. (2001): (Landschafts-) Degradation – Desertifikation: Erscheinungsformen, Entwicklung und Bekämpfung eines globalen Umweltsyndroms. In: Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen, 145 (4), 6 – 15.

- ↑ USGS (2004): Fact Sheet: Landslide Types and Processes.

- ↑ BALDENHOFER, K. (2002): Bodenverdichtung. In: BRUNOTTE, E. et al. (Hrsg. u. a.)(2002): Lexikon der Geographie. Heidelberg, Berlin: Spektrum.

- ↑ BAUMHAUER, R. (2007): Desertifikation und Klimawandel. In: GEBHARDT, H. et al. (Hrsg. u. a. ) (2007): Geographie: Physische Geographie und Humangeographie. München, Heidelberg: Elsevier, Spektrum. S. 983 – 987.