Parking Management: A Contribution Towards Liveable Cities

Introduction

Why is parking so important?

The availability and cost of a parking space is an important determinant of whether or not people choose to drive to a particular destination, and also whether they choose to own a car at all. Whilst parking controls and prices are rarely popular with the public, they are policy options that are relatively well-known and accepted even in many cities in developing countries. If there is an obvious shortage of parking spaces then many people may accept that there is a need for parking controls. Parking controls and pricing are transport demand management measures implemented frequently by local authorities.

What’s wrong with parking in many towns and cities?

There are examples of cities in developing countries that do have some parking management in place. However, in many towns and cities parking is not managed at all, mismanaged or managed only in very limited areas. Some of the typical problems faced by cities all around the world, but particularly in developing countries include the following:

- On-street parking causes safety and congestion problems by blocking one or two traffic lanes, narrowing streets to one lane, reducing visibility and forcing pedestrians to walk in the road if no proper footpaths are provided. In addition, it may obstruct access for emergency services.

- Poor management of on-street parking and/ or lack of information about parking availability in areas of high demand lead to large amounts of traffic circulating looking for a parking space, contributing to congestion and pollution.

- Parking regulations are not enforced, or poorly enforced, and enforcement and management is sometimes informal and/or corrupt.

- Where on-street parking is priced, it is often cheaper than off-street parking. As a result, people look for a scarce space on the street whilst off-street car parks lie half empty.

- Town and city centres are concerned about losing custom to edge of town developments with lots of parking, so they respond by trying to make it easier to park.

Parking: some definitions

Parking Demand

The necessity for a car to be parked is called Parking Demand. If the number of cars in a locality, neighborhood or a city increases, so does the demand for parking spaces. The demand further grows when a majority of the cars in the locality are in transit, as they need more than one parking place. Parking problems begin to arise when demand for parking space exceeds supply. Typically, town and city centres are where these problems occur first, and then they spread outwards from there.

Qualified demand

It is common in medium and larger cities that in certain places at certain times demand for parking exceeds supply. In this situation, the question arises: which users should have access to the limited parking available?

- Residents are often top of the priority list, due to their political importance at the local level. Residents will be given preferential access to on-street parking and/or reduced rate access to off-street parking.

- Business visitors, tourists and shoppers are next in line for access to space, although – where charging exists – they will be expected to pay more than residents.

- Commuters are last in line for access to on-street parking especially, because they are seen to contribute most to rush hour congestion.

- Deliveries also need kerbspace which means giving them access to the kerb at some time of day, although this can be negotiated – it might be at night, or early in the morning

Parking management strategies

Introduction: matching problems and solutions

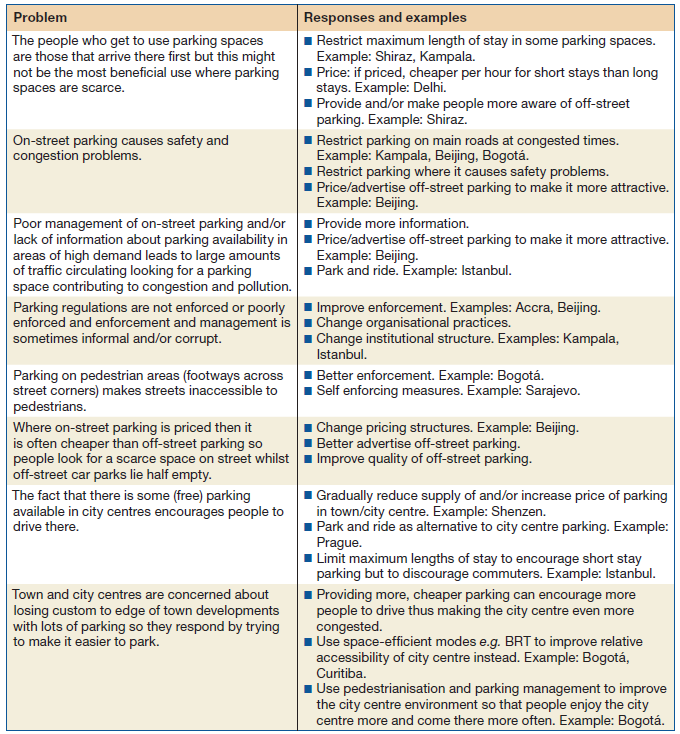

The following table is a form of decision support guide. On the left is a list of typical parking problems. On the right are some actions that can be taken to deal with these issues.

Using parking to achieve transport objectives – developing a parking policy

Introduction

There is a tendency in many cities in developing countries to deal with parking management in a rather reactive way. If a parking problem appears in an area parking management is implemented in that location only to deal with the specific problem. However, if parking is addressed in a more strategic way, then it can be used very effectively as a way to help achieve many environmental, social and economic objectives. National transport policies have remarkably similar objectives across many countries.

The following are typical:

- Developing the local and national economy and making city centres attractive for economic activities;

- Reducing car use to reduce congestion;

- Encouraging the use of alternatives to the car;

- Improving public transport, including its integration with other modes, especially in larger towns and cities;

- Reducing the environmental impacts of car use;

- Making sure that transport is fully accessible for all groups of the society.

Development of a typical parking policy

Stage 1 – no problems, available parking space is gradually used up.

Stage 2 – as demand starts to exceed supply in certain streets, so regulations are introduced in those streets. Parking may be prohibited in some locations, more clearly marked in others.

Stage 3 – as demand further increases, some form of time limit is introduced in towns and city centres, in order to increase the turnover of spaces so that they are more likely to be used by shoppers and visitors, and less by commuters. Disc parking or signed zones may be the initial method used to stimulate turnover, but pricing may then be introduced to further manage the parking stock. Underground and/or off-street parking may also be built at this stage to supplement and replace on-street parking.

Stage 4 – commuters are pushed into surrounding areas. Competition with residents for parking space develops. Residents’ zones are introduced to deal with this.

Stage 5 – more and more differentiation of parking tariffs is introduced to target different groups, and to encourage use by one group more than another.

Stage 6 – development of park and ride facilities on edge of town.

Stage 7 – inclusion of parking in transport demand management.

Aligning the parking policy with a general Transportation Demand Management strategy

As elaborated, parking management is one powerful tool to address urban development objectives and in that sense to address transport demand. However, it is only one tool among many others. In order to maximise the impact of parking management, the objectives and elements of the parking management strategy need to be closely aligned with other elements of the general Transportation Demand Management (TDM) strategy. Parking management measures can act as PUSH-factors to support the shift to public transport and to avoid unnecessary trips.

Relationship between parking and public transport use policies to encourage public transport

It has generally been found that parking policy measures are likely to be relatively more important than many other traffic management measures in influencing how people choose to travel.

Supportive vehicle parking policies will be essential to complement other transport initiatives in achieving objectives relating to accessibility and the environment. If there is an excess of city centre parking over demand for it, improvements in public transport alone cannot be expected to result in a change in modal split. Many of the most significant initiatives and policies towards city centre transport depend for their success on restricting road traffic, and parking policy is one of the most potent yet also publicly acceptable means of restriction.

Measures to deliver your parking policy and achieve objectives

- Start controls where demand is highest – which may be one or two streets only.

- Start prices low, but remember that you can increase them from that level until occupancy levels are optimised (with around 85 % of spaces full at peak times – this guarantees that it is relatively easy to find a space).

- Keep maximum durations 3–4 hours in shopping/business areas so that commuters cannot park there and spaces are used several times a day by different shoppers and business visitors.

- Decriminalise enforcement (so that it is no longer the responsibility of the police). This is normally found to make enforcement more effective.

- Price off-street parking lower than on-street and make people aware of that, so that they are encouraged to use the former.

- Make clear to people how the revenue generated from parking is used, to increase the acceptability of charging

- Have maximum but not minimum parking standards for the amount of parking required to be built with new buildings (or do not allow new parking spaces with new developments, e.g. in dense urban areas with good public transport accessibility).

Regulating and managing on-street parking

Where the legislation to regulate on-street parking exists, it is normally the local authority which decides on the parking regulations. There is a general tendency for on-street parking regulations to become more stringent (restrictive), the closer that one goes to the centres of towns and cities – because these are the areas of greatest demand. The vast majority of on-street spaces in any country remain un-regulated in any way, because demand is less than supply.

- No parking at any time around the mouths of junctions in order to ensure sightlines for vehicles, and safety and access for pedestrians crossing.

- Parking restrictions on main roads at peak hours to facilitate traffic flow.

- Parking restrictions on one side of a narrow road to permit two-way traffic flow.

- Time limited on-street parking in order to facilitate the turnover of parking spaces – usually to ensure that short term parkers (e.g. shoppers) can get a space. Maximum stays might be set at 30 minutes, 1 hour or 2 hours, depending on demand.

- Parking restrictions in certain areas to provide kerb space so that commercial vehicles can load and unload to service shops and offices alongside the road (see further details in next section).

- Time limits around stations (e.g. no parking 13:00–14:00 on weekdays) to stop informal park and ride if this activity is not desired by city authorities.

- Use parking as one tool for traffic calming: Parked cars can help to slow down traffic – however, careful implementation in view of traffic safety is needed.

- Bicycle parking: Require bicycle parking in new development, and allow bicycle parking to substitute for minimum automobile parking in zoning codes.

Loading for commercial vehicles

It is very important for a functioning local economy that commercial vehicles can stop onstreet to load and unload deliveries to shops and other businesses that do not have space for loading and unloading within their own building area. Conversely, it is also important for traffic flow, safety and the environment that such vehicles cannot always stop exactly when and where they choose to do so – some compromise is usually required. This is normally in the form of time limited loading (e.g. maximum stay 15 minutes) and bans on loading at peak hours, on main roads (to allow traffic to flow), or in main shopping hours (on pedestrianised shopping streets). Such restrictions must be well-signed and companies informed so that they know the restrictions; but good enforcement is also necessary.

Managing off-street parking

From the point of view of reducing the visual impact of on-street parking, reducing congestion from search traffic and in some cases reallocating surface street area from parked cars to pedestrians, there are considerable attractions in constructing new off-street public parking, but the construction costs are significant. The key point to highlight here is that such high charges are required to make a profit on the investment that it is difficult to set a price that is attractive in relation to on-street parking. This means that the off-street car park will have to be subsidised if it is to be used – but the local authority may decide that the subsidy is better targeted at public transport or park and ride In addition, from a policy point of view, the provision of new off-street car parks in central areas of cities can exacerbate problems of congestion, because the new ease of parking may encourage more people to drive. This means that it makes sense to consider whether it can be replaced by parking further out of town with good public transport links in – park and ride. Some recommendations about public off-street parking are as follows:

- Consider carefully whether it is really needed or whether it can be provided instead by parking further out of town (park and ride) and good public transport links. If the decision is taken to provide public offstreet parking in or close to the city centre, then:

- Make sure it is near to where people want to go – an obvious but often overlooked point.

- Even if a private operator runs the car park, ensure that the local authority can influence the pricing structure.

- Set prices lower per hour for short (up to 3–4 hours) and much higher per hour for long stay, to encourage turnover of spaces and to deter commuters.

- Set prices lower than the price of on-street parking. If on-street parking near the new off-street car park is very cheap or free with no time limits, almost nobody will use the new off-street car park.

- Make sure that traffic to and from the entrances and exits to the car park does not cause congestion, especially for public transport.

- Once the car park is open, reduce/remove on-street parking to compensate, especially in areas where people searching for car parking and manoeuvring into spaces was causing congestion.

Institutional issues and enforcement

Institutional issues

International experience shows that a private organisation working under the roof of the public administration seems to be the best form of organisation for parking management. In this setting, the public authority retains control over policy and strategy (e.g. the total supply of on- and off-street parking), and over important issues of policy such as the level of fines, and whether fines should vary according to the severity of the parking violation.

The tasks of the private organisation should include:

- Inventories and forecasts for both parking supply and demand.

- Provision of on-street parking supply (design, road markings, sign posting).

- Operating public off-street parking facilities/ Control on public off-street parking facilities.

- Definition of terms of use for on-street parking.

- Operation of controlled on-street parking.

- Parking enforcement should be handled by a separate organisation which also should be organised as a private company under the roof of the public administration, at least if the national law allows this. If not, this entity has to be part of the local administration.

The tasks of this organisation are:

- control of parked areas in areas with specific regulations (time restrictions, parking fees),

- issuing of the fine tickets, and

- control of the payment of the fines.

Enforcement

The key point to remember about enforcement is that it can and does improve. Some political will is required but it is normally the case that if enforcement changes a chaotic situation to one that is more orderly, people see the benefit and accept it.

Implementation – Gaining acceptance for new parking policies

Small and/or incremental (step by step) change is likely to be more accepted than a large sudden change. But in any case, the public must be “carried along” with the changes, and whether they are or not will depend to a large degree on the communication that has been carried out. Effective communication involves broad participation of those with an interest in parking in the change process; a monitoring process, so that people know what the effects of parking changes are, as those changes are introduced; management of complaints, as part of communication; and the use of new forms of communication (e.g. special meetings between politicians and key stakeholders). The public’s acceptance of parking policy changes will in general depend on whether a number of factors are in place, as follows

- That they know and understand the measures.

- That they perceive that there will be a benefit, in terms of the solution of a problem – and that parking fees and other regulations are related to the scale of this problem.

- That there are alternatives to parking (in the controlled area), such as park and ride, or better public transport services.

- That the revenue will be allocated fairly and transparently (people know where it has gone).

- That the parking regulations will be enforced consistently and fairly, and that fines will not be excessive (and, ideally, that the fines are related to the seriousness of the offence – for example, overstaying on a parking meter would be a lesser offence than parking illegally in a bus lane).

Recommendations

As car ownership grows, so demand for parking will grow, and most towns and cities will have to deal with many environmental, social and economic impacts. It is possible to develop a car parking policy that will manage the negative impacts of urban car use whilst also supporting business and the economy.

The following recommendations can be drawn based on numerous studies around the world:

- That the role for parking as a means of restraining car use should be recognised in transport policy documents and actions and needs to be included in a comprehensive manner.

- That there is a need for national maximum parking standards (expressed as guidance) for new development.

- These national guidelines should be translated to regional maximum standards.

- Legislation is needed to set a framework for parking charges and fines, and to put liability for any fine with the owner of the car.

- Legislation should provide local authorities with the powers to enforce parking regulations if they wish, and to keep the revenue so generated, and to follow up those who do not pay fines, and to contract out the parking enforcement operation.

- As demand for parking increases there will be an increasing need to introduce paid parking. Thus, managing demand on a long run.

- Parking tariffs should be higher for on-street than off-street, to encourage people to use the latter.

- Park and ride has a role to play in maintaining the accessibility of central areas of larger towns and cities, but it will work best where there is a shortage of central area parking.

- All changes to parking must be communicated well in advance.

- A positive approach towards working with the public may increase compliance with parking regulations.

- Periodic evaluation of the project is essential, to have an idea for future improvement.

Further Information

Further and more detailed information can be found on the homepage of the Sustainable Urban Transport Project. The Sustainable Urban Transport Project aims to help developing world cities achieve their sustainable transport goals, through the dissemination of information about international experience, policy advice, training and capacity building.

References

Tom Rye 2010, Parking Management: A Contribution Towards Liveable Cities,