Community Power

Overview

The challenge for the world in general, and Africa in particular, is to make a transition towards clean, democratically controlled, participatory and distributed renewable energy sources. That means moving away from the centralised energy systems to decentralised renewable solutions. Use of Community Power implementation will bring even more benefits to local communities. [1]

This articles summarises the definitions, dynamics and feasabilty of community power projects. Furthermore, it explains what type of support is need to scale up community power outreach. Examples are the German Energy Transition and the initiative to bring those experiences into project development in Africa.

What is a Community-based Energy Project?

Community-based energy projects, also known as community energy (initiatives), include energy production, collective procurement, distribution or conservation of energy. Such projects are determined by their governance structure, participation, ownership, local consumption and technology. There are several models of community energy: local individuals investing in renewable energies, citizen wind parks or electricity or heating cooperatives (Kalkbrenner and Roosen, 2016).[2]

Defining ‘Community’

http://www.dictionary.com/browse/community

The term ‘community’ in the context of community-based energy projects refers to social geographic entities. However, the geographic definition is over-simplistic and communities are likely to be more accurately defined in terms of a political and social process (Dalby and Mackenzie, 1997).[3]

Definitions of Community Energy

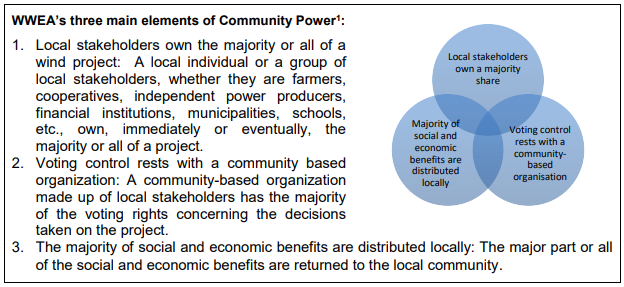

There are many different models all over the world (Germany, other european countries, Japan, but also developing countries). Therefore, there are numerous definitions of and approaches to community energy worldwide. The WWEA defines community energy as “the economic and operational participation and/or ownership by citizens or members of a defined community in a renewable energy project”. Further they state community energy appears in both large and small scale. WWEA also claims that a minimum of two of the following criteria must be fulfilled for it to be community energy initiative (IRENA Coalition for Action, 2018; Schick et al., 2016; Tenk, 2018)[4][5][6]:

Rogers et al. (2008)[7] define a rural community energy scheme as an “installation of one or more RE technologies in or close to a rural community, with input from members of that community”. Further, they claim that the definition of community renewable energy project is flexible. The term is applied to various types of schemes by different groups.

Also (Seyfang et al., 2013)[8] claim that defining the term ‘community energy’ is difficult since there is no consensus over it. The degree of community involvement varies between the understanding of policymakers, intermediary organisations, academics and practitioners have of it. However, they interpret it as projects where communities of place or communities of interest are highly involved and have a high degree of ownership.

Seeking for a definition of the word community in the context of renewable energy projects Walker and Devine-Wright identified two main dimensions taking into account the views of project participants, activists, administrators, policy makers and local residents:

“First, a process dimension, concerned with who a project is developed and run by, who is involved and has influence. Second, an outcome dimension concerned with how the outcomes of a project are spatially and socially distributed—in other words, who the project is for; who it is that benefits particularly in economic or social terms.”[9] (Walker and Devine-Wright, 2008).

Nonetheless, these dimensions do not refer to the technology itself, but to the social arrangements through which a given technology is being implemented (Walker and Cass, 2007).[10]

Common characteristics are also described as the following:[11]

- Ordinary people or citizens are involved in running the project through communities such as co-operatives or development trusts;

- there is a co-operative, democratic or specifically non-corporate structure;

- there are tangible local benefits to people living or working close to projects;

- the profits go back to the community or are re-invested in other community energy schemes

Furthermore, there is a diversity of community power projects regarding the ownership before, during and after inception of the project. What about community-based projects that rather hand off the operation and ownership to a private firm in order to guarantee sustainability of the project? Are those considered to be community-based projects afterwards?

Objectives and Challenges of Community Energy

Especially renewable energy systems present possibilities for local governance of energy production since their social impact is very different from that of fossil-based conventional systems (van der Schoor and Scholtens, 2015).[12] Therefore, the literature mainly discusses community-based projects with regard to renewable energies.

A community renewable energy project must benefit the community either directly or indirectly. Direct benefit results through supply of energy to numerous properties or a community facility. Indirect benefit could arise e.g. by selling energy generated to the grid (Rogers et al., 2008).[7]

Challenges that are faced during the whole process of creation and implementation of community-based energy projects are the following:

- group can lack clear direction or management

- project needs skills, information, financial and material resources

- community must first overcome public disinterest and mistrust of new energy systems and needs to tackle a sense of disempowerment in the public

- a network is necessary to consolidate learning and skills so they can be transferred to others; and

- policy support is crucial; often inconsistent and hard-to-access grant funding; possible difficulties with planning and other legal issues[8](Seyfang et al., 2013)

"In some circumstances, community-managed and -operated mini-grids may be able to provide cheaper electricity to rural communities (Yadoo, 2012). They also give the opportunity for multiple advantages to accrue to the local population such as: empowerment through local management; payment for feedstock; or, if grid-connected at a later stage, income from feed-in tariffs and the potential to leapfrog into a more resilient electricity network (Yadoo and Cruickshank, 2012)."[13]

"There is usually a lack of technical expertise within the community, therefore planning, design, and implementation is done by third parties. To ensure the sustainability of such models, it is important to charge tariffs that at least cover some of the main operation, maintenance, and depreciation costs. Decision making is likely to be localised in such models, however, this depends on the scale of operation. Furthermore, it is important to ensure that the requisite skills to operate and maintain the mini-grids are available in the local area. In the absence of adequately trained human capital such grids are likely to be unsustainable. It will provide opportunities for what Tenenbaum et al. (2014: 25) refer to as “boutique electrification”, which implies that it does not lead to sustained and significant electrification (ibid.)."[13]

Dynamics of Community-based Energy Projects

Building a community energy project is very complex, whichever development model is applied. Legal conditions as well as economic and technical viability have to be taken into account. Receiving support and advice from experts and learning from previous experiences is substantial (Walker, 2008).[14]

Trust plays a substantial role in the implementation and outcome of community RE projects Walker et al. (2010)[15] showed. Trust can even be enhanced by following a communal approach. However, this conclusion cannot be generalised and trust and the cohesion between the local residents cannot be ensured just because the project has a community label.

In an empirical investigation on the terms of motivations and level of engagement of members of community renewable energy projects the analysis revealed diversity in the members’ motives. This heterogeneity can be explained by three aspects:

- institutional factors ⇒ members are norm-driven when community logic is paramount, whereas material incentives are motivational for the members when they are connected through a market relationship with the organisation

- spatial patterns ⇒ communities of interest are less likely to foster norm-driven behaviours than communities of place

- attitude towards the diffusion of institutional innovations

Lastly, it was concluded that norm-driven individuals are the ones who are more involved and invest more in the governance of organisations. Thus, the diversity of motivations also depends on the level of engagement of members (Bauwens, 2016).[16]

Cultural Success factors of local community energy projects:[17]

- history of locally activism

- local people already own things together (e.g. soccer field or pub)

- strong culture of social enterprise

- other aspects

Feasibility of Community Energy Initiatives

From a study on rural community energy schemes carried out in the UK Rogers et al. concluded that local control of projects might not be a realistic option for many rural communities. Despite the concept itself being popular and people finding the participant role attractive:

- majority was interested in participation, and yet nobody wanted to take on the role of the project leader

- then again residents did not think community control was a viable option due to negative experiences with other local initiatives

- residents who showed interest did not know how or where to find specialists nor how to develop specialist knowledge and skills themselves

► required: more institutional support needed to enable and further projects and participation (Rogers et al., 2008)[7]

Van der Schoor and Scholtens (2015)[12] similarly concluded that to achieve lasting results further development of organisational structures and viable visions for local energy governance.

Research/Literature on Community-based Energy Projects

The research concerning this topic largely investigates community energy initiatives implemented in the Global North (e.g. US and EU). These projects mainly emerge as grassroot approaches enabling citizens to engage in the transition to a sustainable energy future. The dynamics observed and lessons learnt in these initiatives might not be explicitly translatable to the implementation of community-based energy projects in developing countries. The composition, objectives and the business models are different in these two contexts (Koirala et al., 2016).[18] Further, Kirubi et al. (2009)[19] pointed out the limited amount of empirical case studies of rural electrification programs in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly community-based projects.

Conclusion: Supporting Structures are needed

In order to overcome the challenges, to steer the dynamics in a favorable way and to make community power project feasible and scalable, several supporting mechanisms should be placed in the foreseeable future:

- Policy support within all countries that want to enforce community power projects to establish appropriate regulatory environment and proper design

- Network support to consolidate learning and skills so they can be transferred to others (knowledge management).

- Collection of all the community power projects globally, sort them by different categories of the definition that includes the broaden variety of projects:

- Identify successful projects and their stories to learn from (see database coming soon)

- Identify relevant communities, organizations, companies and individuals interested in participating in community power projects

- Build strong partnerships between successful community power project and new community power projects

- Research facilities should be strengthened to facilitate research about the behavior and conditions that lead to successful community power projects

- Community, projects, individuals all need guidance on how to best structure and steer the development of community power projects and to further develop organizational structures and viable visions.

IRENA (2018) calles for the following actions to promote community power:[4]

- policies to incentivise decentralised, integrated, community-based renewable energy systems

- set specific "community" targets for tendering and auction processes

- include also macro-economic costs into long-term energy plans

- target the correct group of community projects (definitions are key!)

- establish community energy authorities

- assist in development of alternative business plans (eg. via public guarantees)

- international programmes and initiatives should include community power into their work

- international finance organisation could establish a facility dedicated to community power

- networking event to foster learnings from pilots and among different countries

Global trends

Across the world, community initiatives change our existing energy sector by producing, selling, and distributing renewable energy or delivering energy services. In Europe, more than 2,800 energy cooperatives were in operation as of 2015. Australia has 45 community energy projects and 70 are in planning phase. In India, community energy projects (largely micro-hydro) have existed since the 1950s and in Nepal, roughly 15% of electricity is produced by community-owned micro-hydro installations. Costa Rica, with its ambitious goal of becoming carbon-neutral in 2021, is home to four energy co-operatives with over 180,000 members, controlling almost 15% of the energy market. In East Africa, where community energy projects have driven energy access efforts in areas that lack a centralized electricity grid.[20]

Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s women-owned Coastal Electrification and Women’s Development Cooperative (CEWDC) was formed in 1999. Members of the co-operative manufacture and sell solar lamps and charge controllers for solar home systems (SHS), as well as batteries, and they provide energy to the off-grid rural community of Char Montaz and four surrounding islands. The local women are both providers and users of the solar energy and earn a monthly wage for assembling the SHS.[21]

Mali

SharedSolar provides electric infrastructure and service to off-grid communities through a combination of renewable energy, smart metering and storage management, and has built micro-grids for communities in Mali (since 2010) and Uganda (since 2011). Local energy co-operatives and community-owned partnerships are established under a pay-as-you-go model.[22]

India

Jakson Engineers LTD - Solar Powered Village (Baripatha) Electrification

Jakson Engineers is a diversified power solution provider that undertakes projects for sustainable growth. This project in Baripatha, India, created a solar-powered village in India with the installation of central, and individual solar units.This community-owned project has improved the quality of life of an entire rural village. The villagers clean the solar panels and maintain battery water levels themselves. The solar unit can be folded up and stored in just two minutes in case of cyclones or high winds. The provision of microfinancing was a key component to the project’s realization, which will help the long-term success of the project.Although not extraordinarily technically innovative, it is a replicable off-grid application that reduces pollution and reliance on kerosene. This overwhelming social and environmental impact convinced the jury of its outstanding character.[23]

Kenya Mini-grids

In Kenya’s community owned mini - grids, the community is responsible for the operation and maintenance of the whole system, from generation to transmission and collection of dues. In general, the communities have management committees comprising of a chairman, vice chairman, a treasurer and a manager responsible for technical operation of the whole system. Further, payment collection is face - to - face where by member(s) of the committee move from house to house collecting payments. Collecting revenue this way presents challenges owing to high rates of default. Therefore there is good potential for the application of remote monitoring, control and payment technologies for community owned mini - grids in Kenya though important barriers exist related to skills and capacity as well as the cost of the technology.[24]

Brazil

Brazil has a strong tradition of cooperatives, with currently more than 6,600 cooperatives and more than 13 million associates. This provides a great opportunity for distributed renewable energy generation. Recently, the national electricity regulator ANEEL introduced a norm that allows the net-metering scheme to be used not only by households but also by cooperatives and condominiums. The German experience with the business model of renewable energy cooperatives has strongly been utilized within a close collaboration with the German Cooperative and Raiffeisen Confederation (Deutscher Genossenschafts- und Raiffeisenverband, DGRV). [25] See Renewable Energy Cooperatives in Brazil

Future of Community Power in Afrika

In addition to large power plants, Africa will also need decentralized mini-grids and “green people’s energy” in order to build anrenewables-based energy supply. The German Development Coopertation wants to help set up thosewith enhancing the energy cooperation with African countries during the next 5 years. "Green people’s energy” for Africa is the answer that can help meet the rising demand for energy across the African continent while preventing the devel - opment of a high-carbon energy sector. Sun, wind, biomass and hydropower are available in abundance. Everyone can benefit from these sources of energy and from the expansion of energy access.[26]

Germany can draw from its own experience: In the 19th century, energy cooperatives were a driving force behind rural electrification in Germany. And also the recent energy transition was only thanks to the dedicated efforts of citizens, municipalities and SMEs that renewable energy sources were developed on a massive scale. Nearly 900 energy cooperatives are active in energy projects of this kind. Bioenergy villages, municipalities that are energy self-sufficient, municipal utilities that belong to the people, and citizens who produce their own energy form the backbone of the energy transition: Most of Germany’s renewable energy installations are owned by individuals, municipalities or farmers.[26]

Germany wants to pass on the lessons we have learned. Green people’s energy is possible, especially in Africa, but it requires an appropriate regulatory environment and proper design. Germany has a strategy how to incorporate their expertise into development cooperation at all levels for the benefit of Africa, based on strong partnerships for people’s energy and intermunicipal cooperation arrangements.[26]

Community power has a proven, very positive impact on deployment rates of renewable energy and increases the economic and social benefits of renewable energies for local communities and their actors. It increases community acceptance, involvement and benefits from renewable energy installations, and has been key driver in pioneering European countries adopting renewable energy. Community Power has the potential to boost renewable energy adoption in Africa, which has currently the lowest electrification rates and population densities in the world. The decentralised renewable resources can be matched with decentralised populations and can have a real and measurable impact on Africa’s living conditions and economic development while providing incentives allowing people to live in regions already affected by climate change.[27]

In 2018, the leading community power proponents around the world together to discuss the role community power has to play in the global shift towards renewable energy, including a global community power strategy and its national and local implications.

- 2° World Community Power Conference will take place 8-10 November 2018 Bamako - Mali

The 1st World Community Power Conference 2016 took place in Fukushima City, Japan. The conference concluded with the “Fukushima Community Power Declaration – for the future of the earth” which was agreed by the more than 600 participants from more than 30 countries, to support community power. The declaration mentions that sustainable energy is essential to future wellbeing of all and that the implementation of this renewable energy future must respect local and regional needs and priorities, as well as existing societal, cultural and environmental conditions, and, in other words, follow the principles of “community power."[28] One afternoon focussed on Community power in Africa.

Further Readings

- Feature Community: GSR 2016

- BMZ: Green people’s energy for Africa

- IRENA: Community Energy

- WWEA: Community Wind

- World Community Power Conference in Mali, Nov 2018

- Lessons learnt from community-based pico- and micro-hdyropower schemes

- Participatory Management (PM) Approach for Achieving Rural Electrification. Nepal

- Community Based Rural Electrification – Micro Hydro: Tungu-Kabiri Pico-Hydro Project, Kenya

- Mini-grid portal on energypedia

- Community Involvement in Mini-grids

- German Success factors of the Energy transition#Citizen-owned_Projects and Citizen participation models in Germany#Bankability_and_Project_Financing

- Community Engagement for Power Projects

References

- ↑ https://www.conference.community/context-and-background/

- ↑ Kalkbrenner, B.J., Roosen, J., 2016. Citizens’ willingness to participate in local renewable energy projects: The role of community and trust in Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 13, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.12.006

- ↑ Dalby, S., Mackenzie, F., 1997. Reconceptualising local community: environment, identity and threat. Area 29, 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.1997.tb00012.x

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 IRENA Coalition for Action, 2018. COMMUNITY ENERGY: Broadening the Ownership of Renewables. IRENA.

- ↑ Schick, C., Gsänger, S., Dobertin, J., 2016. Headwind and Tailwind for Community Power: Community Wind Perspectives from North-Rhine Westphalia and the World. WWEA Policy Pap. Ser. PP-01-16.

- ↑ Tenk, F., 2018. Community Wind in North Rhine-Westphalia: Perspectves from State, Federal and Global Level. WWEA Policy Pap. Ser. PP-01-18.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Rogers, J.C., Simmons, E.A., Convery, I., Weatherall, A., 2008. Public perceptions of opportunities for community-based renewable energy projects. Energy Policy 36, 4217–4226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.07.028

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Seyfang, G., Park, J.J., Smith, A., 2013. A thousand flowers blooming? An examination of community energy in the UK. Energy Policy 61, 977–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.06.030

- ↑ Walker, G., Devine-Wright, P., 2008. Community renewable energy: What should it mean? Energy Policy 36, 497–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2007.10.019

- ↑ Walker, G., Cass, N., 2007. Carbon reduction, “the public” and renewable energy: engaging with socio-technical configurations. Area 39, 458–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2007.00772.x

- ↑ http://www.communitypower.scot/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CommunityPowerScotlandOct2014Web.pdf

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 van der Schoor, T., Scholtens, B., 2015. Power to the people: Local community initiatives and the transition to sustainable energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 43, 666–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.10.089

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 https://e4sv.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/TR9.pdf

- ↑ Walker, G., 2008. What are the barriers and incentives for community-owned means of energy production and use? Energy Policy 36, 4401–4405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.09.032

- ↑ Walker, G., Devine-Wright, P., Hunter, S., High, H., Evans, B., 2010. Trust and community: Exploring the meanings, contexts and dynamics of community renewable energy. Energy Policy 38, 2655–2663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.05.055

- ↑ Bauwens, T., 2016. Explaining the diversity of motivations behind community renewable energy. Energy Policy 93, 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.03.017

- ↑ British Academy 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mrMRwJGoHAc

- ↑ Koirala, B.P., Koliou, E., Friege, J., Hakvoort, R.A., Herder, P.M., 2016. Energetic communities for community energy: A review of key issues and trends shaping integrated community energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 56, 722–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.11.080

- ↑ Kirubi, C., Jacobson, A., Kammen, D.M., Mills, A., 2009. Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 37, 1208–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.005

- ↑ A Record Breaking Year for Renewable Energy – and Community Energy 2016, https://www.worldfuturecouncil.org/record-breaking-year-for-renewables-and-community-energy/

- ↑ CEWDC from US Agency for International Development, Gender Assessment: South Asia Regional Initiative for Energy (New Delhi: February 2010), http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnads874.pdf, from Ashden, “PSL, Bangladesh – Solar co-operative for rural women,” https://www.ashden.org/winners/psl, viewed 28 December 2016, and from Ashden, Case Study Summary: Prokaushali Sangsad Ltd (PSL), Bangladesh (London: December 2009), https://www.ashden.org/files/PSL%20Bangladesh%20case%20study%20full.pdf.fckLRfckLR

- ↑ https://www.intersolar.de/en/for-visitors/exhibition/award/award-winners.html

- ↑ Study by Economic Consulting Associates (ECA) titl ed “ Project Design Study on the Renewable Energy Development for Off - Grid Power Supply in Rural Regions of Kenya", cited in Practical Action 2016 https://infohub.practicalaction.org/bitstream/handle/11283/620304/Market+Analysis+Kenya+and+Rwanda.pdf;jsessionid=C50C3EB31F410EC72E2737A640A04435?sequence=1

- ↑ https://energypedia.info/wiki/Net_Metering_in_Brazil#Renewable_Energy_Cooperatives

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), 2017, BMZ POSITION PAPER 06 | 2017 GREEN PEOPLE’S ENERGY FOR AFRICA. https://www.bmz.de/en/publications/type_of_publication/strategies/Strategiepapier395_06_2017.pdf

- ↑ https://www.conference.community/

- ↑ http://www.wcpc2016.jp/en/