Difference between revisions of "Lighting"

***** (***** | *****) m |

***** (***** | *****) m |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

Provided a national power grid exists close to the place of lighting demand, [[Grid|grid extension or densification]] will most likely (depending on local connection costs and tariff structures) be the most cost-efficient way of providing electricity for lighting purposes. In more remote areas away from the grid with appropriate site conditions, [[Hydro|micro hydro]] or pico hydro power installations are generally the best option to provide electricity to small communities (micro hydro) or individual consumers (pico hydro). Due to a generally larger amount of electricity supplied to the individual consumer, grid electricity and micro hydro in addition to lighting services can easily meet other energy demands such as information (TV, radio), refrigeration (e.g. in health centers), or motive power for productive purposes. This has to be taken into account before any cost benefit analysis of energy sources for lighting should be undertaken. | Provided a national power grid exists close to the place of lighting demand, [[Grid|grid extension or densification]] will most likely (depending on local connection costs and tariff structures) be the most cost-efficient way of providing electricity for lighting purposes. In more remote areas away from the grid with appropriate site conditions, [[Hydro|micro hydro]] or pico hydro power installations are generally the best option to provide electricity to small communities (micro hydro) or individual consumers (pico hydro). Due to a generally larger amount of electricity supplied to the individual consumer, grid electricity and micro hydro in addition to lighting services can easily meet other energy demands such as information (TV, radio), refrigeration (e.g. in health centers), or motive power for productive purposes. This has to be taken into account before any cost benefit analysis of energy sources for lighting should be undertaken. | ||

| − | For remote locations away from central power grids and without any hydro power potentials three basic ways of electricity supply for lighting are thinkable: central charging stations, small village-level mini grids, or electricity generation on individual consumer (household, social institution, business) level. | + | For remote locations away from central power grids and without any hydro power potentials three basic ways of electricity supply for lighting are thinkable: central charging stations, small village-level mini grids, or electricity generation on individual consumer (household, social institution, business) level. |

| − | [[Solar Battery Charging Stations|Central charging stations]] can be powered by any electricity source (often PV) and either charge rechargeable lanterns (e.g. LED-based) or batteries (e.g. car batteries) that after charging will be attached to standard light bulbs in homes. In most cases a small fee applies for the user every time a lamp/battery is recharged. Central charging station can also be an option where grid extension is not a cost-efficient option, but the grid is close enough for regularly transporting the lamp/battery to a (mini)grid-powered charging station. | + | [[Solar Battery Charging Stations|Central charging stations]] can be powered by any electricity source (often PV) and either charge rechargeable lanterns (e.g. LED-based) or batteries (e.g. car batteries) that after charging will be attached to standard light bulbs in homes. In most cases a small fee applies for the user every time a lamp/battery is recharged. Central charging station can also be an option where grid extension is not a cost-efficient option, but the grid is close enough for regularly transporting the lamp/battery to a (mini)grid-powered charging station. |

| − | Mini grids can be powered by [[Solar|Solar PV]], wind, biomass, diesel or any hybrid solution most appropriate to local availability of energy sources. Setting up a mini grid can be costly; ownership, management, billing, and maintenance have to be considered and organised within the community. | + | Mini grids can be powered by [[Solar|Solar PV]], wind, biomass, diesel or any hybrid solution most appropriate to local availability of energy sources. Setting up a mini grid can be costly; ownership, management, billing, and maintenance have to be considered and organised within the community. |

A lot of these issues can be avoided by utilizing individual power systems on consumer level, such as [[Solar|Solar Home Systems and Solar Lanterns]] on household/small business level and bigger sized PV systems for social institutions (e.g. health centers). Depending on the system size Solar Home Systems in households and small businesses of about 50-150 Wp can provide power for several lights and even a small TV or radio for 4 to 5 hours per day, bigger PV systems (> 500 Wp) for social institutions can apart from lighting several rooms power a solar fridge or other small appliances. Individual Solar Lanterns are much cheaper, but will provide light only. Compared to other electricity systems, electricity users are often the owners of their system, leading to significant individual investment needs that have to be approached by appropriate financing mechanisms (e.g. micro credit) or public funding (in case of social institutions). Maintenance and after-sales services are crucial for the long-term functioning of individual stand-alone systems. | A lot of these issues can be avoided by utilizing individual power systems on consumer level, such as [[Solar|Solar Home Systems and Solar Lanterns]] on household/small business level and bigger sized PV systems for social institutions (e.g. health centers). Depending on the system size Solar Home Systems in households and small businesses of about 50-150 Wp can provide power for several lights and even a small TV or radio for 4 to 5 hours per day, bigger PV systems (> 500 Wp) for social institutions can apart from lighting several rooms power a solar fridge or other small appliances. Individual Solar Lanterns are much cheaper, but will provide light only. Compared to other electricity systems, electricity users are often the owners of their system, leading to significant individual investment needs that have to be approached by appropriate financing mechanisms (e.g. micro credit) or public funding (in case of social institutions). Maintenance and after-sales services are crucial for the long-term functioning of individual stand-alone systems. | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | <u> | + | <u>Lighting Initiatives and Organisations:</u> |

[http://www.lightingafrica.org Lighting Africa] - a joint IFC and World Bank program that seeks to support the global lighting industry in developing affordable, clean, and efficient modern lighting solutions for Sub-Saharan African | [http://www.lightingafrica.org Lighting Africa] - a joint IFC and World Bank program that seeks to support the global lighting industry in developing affordable, clean, and efficient modern lighting solutions for Sub-Saharan African | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

[http://labl.teriin.org Lighting a Billion Lives] - a TERI campaign to bring modern lighting services to rural areas of India through central charging stations in combination with rechargable PV-lanterns | [http://labl.teriin.org Lighting a Billion Lives] - a TERI campaign to bring modern lighting services to rural areas of India through central charging stations in combination with rechargable PV-lanterns | ||

| − | [http://www.dlightdesign.com/ D-Light] - private company selling small PV lighting products for the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP) market in India; CDM project for LED-based lighting is in the pipeline. | + | [http://www.dlightdesign.com/ D-Light] - private company selling small PV lighting products for the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP) market in India; CDM project for LED-based lighting is in the pipeline. |

[[Www.sunlabob.com|Sunlabob]] – this private company offers a franchise rental system for Solar Home Systems and solar-rechargeable lamps in Laos | [[Www.sunlabob.com|Sunlabob]] – this private company offers a franchise rental system for Solar Home Systems and solar-rechargeable lamps in Laos | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <u>Additional Information and Reference:</u> | ||

[http://www.lightingafrica.org/node/7436 Current Lighting Situation and Market Potential of improved lighting products (2009)] - 'Lighting Africa' Market Studies from Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia | [http://www.lightingafrica.org/node/7436 Current Lighting Situation and Market Potential of improved lighting products (2009)] - 'Lighting Africa' Market Studies from Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia | ||

= Impacts of Improved Lighting Services = | = Impacts of Improved Lighting Services = | ||

Revision as of 09:28, 12 January 2010

The Need for Improved Lighting

Lighting needs in developing countries

Lighting is besides cooking one of the most primal energy needs. Humans have been trying to lengthen their day with artificial lighting for thousands of years. In comparison to industrialized countries where energy for lighting is basically provided by electricity, lighting in most parts of developing countries is still based on fossil fuels. Due to the low efficiency of fuel-based lighting, the quality of provided lighting services is generally very low. This can have negative implications for activities that rely on proper lighting conditions.

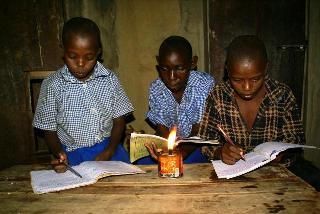

In households, activities such as reading/studying, household work and productive processes (cottage industries) depend on good lighting conditions.

Social institutions are in need of high-quality illumination for a wide range of applications: rural schools use artificial light to provide classes during cloudy days or at night and for staff/student quarters. Rural hospitals and health centres need light for emergency treatments (e.g. childbirth) at night, illumination of surgeries with operating lamps and for staff/patient accommodation. To allow for social gatherings and events after sunset, artificial lighting is often used in town halls or religious buildings. Artificial street lighting is a very convenient way for rural communities to improve security and mobility.

Small businesses use lights when carrying out production in the evening; shops have to illuminate their goods to be able to sell them on evening markets and to attract their potential customers. In certain cases lighting is a crucial factor for reaching the maximum production potentials of livestock (e.g. chicken farming).

'Traditional' fuel-based lighting

Unlike heating or cooking, lighting is one of the energy end uses that is often associated exclusively with electricity. But the reality is different: In fact, about a third of the world’s population uses fuel-based lighting.

Every year, African households and small businesses spend upwards of $17 billion on lighting, dominated by fuel-based sources such as kerosene, a costly an inefficient alternative. However, despite these huge expenditures – many households spend as much as 30% of their disposable income on fuel-based lighting – consumers receive little value in return. Fuel-based lighting is inefficient, provides limited and poor quality light, and exposes users to significant health and fire hazards. Exacerbating this problem, fuel-based lighting also produces Greenhouse Gases (GHGs), leads to increased indoor air pollution and associated health risks, inhibits productivity and jeopardizes human safety.

The state of affairs concerning fuel-based lighting is worrisome. Oil import dependency is generally high in developing countries, and it drains valuable hard currency. Further complicating the picture, subsidized kerosene intended for domestic lighting sometimes finds its way into vehicles, which creates additional environmental consequences.

There are a wide variety of fuelbased light sources, including candles, oil lamps, ordinary kerosene lamps, pressurized kerosene lamps, biogas lamps, and propane lamps. According to most studies, ordinary kerosene lamps are the most common type of fuel-based lighting in developing countries. The more efficient kerosene lamps tend to increase both light output and fuel consumption, whereas an efficient electric compact fluorescent lamp provides an eight-fold reduction in primary energy consumption compared to standard incandescent light sources. According to a 1995 study, typical household kerosene lamp use is 3 to 4 hours per day, with weekly fuel consumption of about 1 litre. Typical light outputs are 10 to 15 lumens for locallymade lamps and 40 to 50 lumens for store-bought models. Placed in perspective, the lower end of this range corresponds to about 1% of the light produced by a typical 100-watt incandescent lamp.

A study conducted by the joint UNDP/World Bank Energy Sector management Assistance Programme (ESMAP) found rural households spending as much as US$10 per month on lighting from candles, kerosene and dry cell batteries. This operating cost is similar to that paid by industrialized households with two dozen bright electric light sources throughout their home.

Between 15 and 88 billion litres of are consumed each year to provide residential fuel-based lighting in the developing world. The primary energy consumed for this fuel-based residential lighting is between 13% and 78% of that used to provide the approximately 400 TWh of electricity consumed for residential electric lighting globally. The cost of this energy ranges from $15 to $88 billion/year (assuming a kerosene price of $1/ litre), or $44 to $175 per household. The amount of light (measured in lumen hours) is approximately 1/1000th that enjoyed by households in the industrialized world (more sources; more efficient sources).

Among the more startling implications of these findings is that users of fuel-based lighting in the developing world spend as much or more money on household lighting as do households in the industrialized world, but receive a vastly poorer level of service. On a percentage-of-income basis, households in developing countries spend many times more for lighting than their counterparts in the industrialized world.

Some argue that the problem of fuel-based lighting is not a priority, given the environmental impacts and costs of other end uses, such as cooking. However, few would dispute that improving the quality and quantity of light available to households in the developing world would yield dramatic social and health benefits.

References:

Mills, E. (2000): Fuel for Lighting - an Expensive Commodity. Boiling Point 45. http://www.hedon.info/FuelForLighting-AnExpensiveCommodity .

Lighting Africa: About Us. http://www.lightingafrica.org/node/23 .

Meeting Energy Needs for Improved Lighting

Improved (safe, healthy, efficient) lighting is primarily based on electricity as an energy source, however basic lighting demands can also be met by biogas where available.

Provided a national power grid exists close to the place of lighting demand, grid extension or densification will most likely (depending on local connection costs and tariff structures) be the most cost-efficient way of providing electricity for lighting purposes. In more remote areas away from the grid with appropriate site conditions, micro hydro or pico hydro power installations are generally the best option to provide electricity to small communities (micro hydro) or individual consumers (pico hydro). Due to a generally larger amount of electricity supplied to the individual consumer, grid electricity and micro hydro in addition to lighting services can easily meet other energy demands such as information (TV, radio), refrigeration (e.g. in health centers), or motive power for productive purposes. This has to be taken into account before any cost benefit analysis of energy sources for lighting should be undertaken.

For remote locations away from central power grids and without any hydro power potentials three basic ways of electricity supply for lighting are thinkable: central charging stations, small village-level mini grids, or electricity generation on individual consumer (household, social institution, business) level.

Central charging stations can be powered by any electricity source (often PV) and either charge rechargeable lanterns (e.g. LED-based) or batteries (e.g. car batteries) that after charging will be attached to standard light bulbs in homes. In most cases a small fee applies for the user every time a lamp/battery is recharged. Central charging station can also be an option where grid extension is not a cost-efficient option, but the grid is close enough for regularly transporting the lamp/battery to a (mini)grid-powered charging station.

Mini grids can be powered by Solar PV, wind, biomass, diesel or any hybrid solution most appropriate to local availability of energy sources. Setting up a mini grid can be costly; ownership, management, billing, and maintenance have to be considered and organised within the community.

A lot of these issues can be avoided by utilizing individual power systems on consumer level, such as Solar Home Systems and Solar Lanterns on household/small business level and bigger sized PV systems for social institutions (e.g. health centers). Depending on the system size Solar Home Systems in households and small businesses of about 50-150 Wp can provide power for several lights and even a small TV or radio for 4 to 5 hours per day, bigger PV systems (> 500 Wp) for social institutions can apart from lighting several rooms power a solar fridge or other small appliances. Individual Solar Lanterns are much cheaper, but will provide light only. Compared to other electricity systems, electricity users are often the owners of their system, leading to significant individual investment needs that have to be approached by appropriate financing mechanisms (e.g. micro credit) or public funding (in case of social institutions). Maintenance and after-sales services are crucial for the long-term functioning of individual stand-alone systems.

For the case of biogas digesters, lighting is in most cases not the primary energy end-use, as most of the gas is normally used for cooking. Investment in a biogas plant for lighting purposes only is a very rare occasion and most likely not cost-efficient. However, when being installed for meeting cooking energy needs, biogas plants can be a very convenient way of additionally providing lighting.

Many suppliers of energy-efficient lighting equipment have not found the rural markets in developing countries worth exploring. However, the large amounts of money spent on lighting fuel indicates that there is a considerable potential for spending money on alternatives, for instance PV-based lighting solutions; this was verified in a field test by the World Bank.

For the use of provided electricity for lighting purposes, several types and sizes of lamps are available. The HERA Guide on Lighting Technologies provides an overview and guidance on choosing the right lighting devices.

Lighting Initiatives and Organisations:

Lighting Africa - a joint IFC and World Bank program that seeks to support the global lighting industry in developing affordable, clean, and efficient modern lighting solutions for Sub-Saharan African

Lighting a Billion Lives - a TERI campaign to bring modern lighting services to rural areas of India through central charging stations in combination with rechargable PV-lanterns

D-Light - private company selling small PV lighting products for the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP) market in India; CDM project for LED-based lighting is in the pipeline.

Sunlabob – this private company offers a franchise rental system for Solar Home Systems and solar-rechargeable lamps in Laos

Additional Information and Reference:

Current Lighting Situation and Market Potential of improved lighting products (2009) - 'Lighting Africa' Market Studies from Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia